The base of many performance strategies lies in the gym; but how do we ensure that this is planned and executed as effectively as possible?

The use of structured strength and conditioning within soccer is increasing every season and it is becoming more of a priority within a club’s weekly training. There was a time where strength and conditioning, especially in a gym setting would be put to one side and seen as something that players do as extra work after training, or as part of a rehab programme. However, that way of thinking has been flipped and players now have detailed, planned out, specific gym programmes as part of normal training. This integration has happened in part due to the extensive research into the effect of strength and conditioning work on soccer performance, and due to the financial increases within the game allowing many clubs to own state of the art gym facilities at their training grounds.

In this section we will discuss:

- The science behind strength and conditioning within soccer

- Soccer specific exercises to add into players gym programmes

- How these exercises improve performance

- Scheduling gym-based training into weekly training

Although soccer is an intermittent sport, with most of the energy production coming from the aerobic system, it is still vital that players have good base strength developed in a gym setting. Not only does strength transfer to players’ power, change of direction, and agility performance, but research shows that higher strength and power are major discriminators between elite and sub-elite players, meaning those with higher strength are more likely to reach a higher level [62]. Research also shows that 83% of goals are preceded by at least one powerful action by the scoring player [20], with 45% of these being straight sprints. As discussed in the testing section, we know that strength performance is highly correlated with sprint performance (r = 0.94) [30]. From the information available to us, we have a detailed understanding of how strength and power aid soccer performance, and we therefore have a robust rationale for using gym-based training to improve players muscular strength.

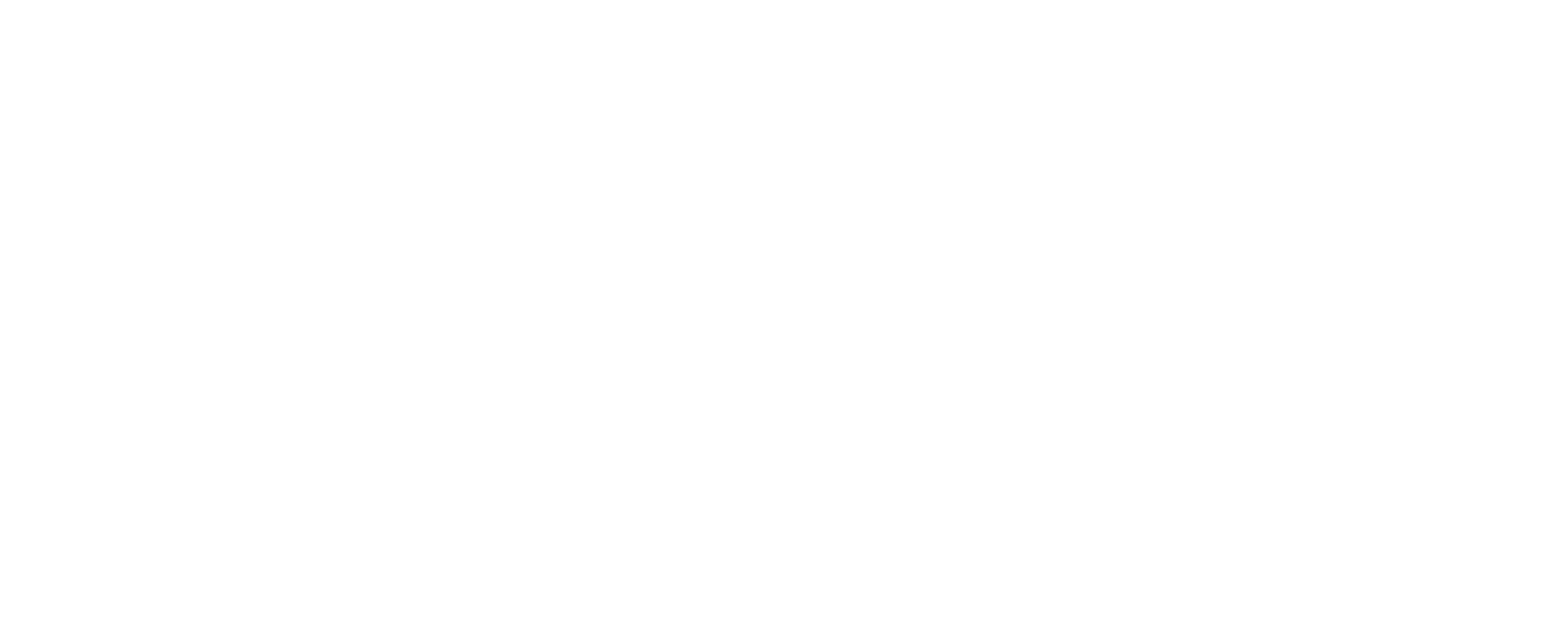

Possibly the most common exercises soccer players perform are squat and hinge pattern exercises, for example, the barbell back squat and the hex-bar deadlift. These are commonly used due to their ease of implementation, and their transferability to soccer performance as research shows that developing high levels of lower-body strength improves sprint and jump ability in soccer players [12], which are important factors in soccer performance. For example, back squat programmes have been shown to improve athletic performance in soccer players, with only 2 sessions per week [11]. Likewise, improvements in maximal squat strength have been shown to improve maximal and relative strength, countermovement jump (CMJ) performance, and short-distance (> 20 m) and longer distance (30 – 50 m) sprint performance, during the competitive season [14][66]. Deadlifts using a hex-bar are also commonly used for improving lower-body strength as the hex-bar makes it easier for players to learn the correct technique and load the exercise compared to a traditional bar or a back squat. The Romanian deadlift can be used to eccentrically load the hamstrings, which is recommended as a hamstring injury prevention exercise [73]. Examples of how these exercises can be progressed and regressed can be found in the Table below.

Studies using soccer players have found that using a unilateral strength training programme improves performance in the countermovement jump test (which is discussed in the testing section), and single leg jump tests. Asymmetry between legs on single leg vertical and horizontal jump tests were found to be decreased by doubling exercise volume on the weaker leg [23]. As we know these tests are related to soccer performance, coaches and staff should consider implementing unilateral strength exercises into players’ gym programmes.

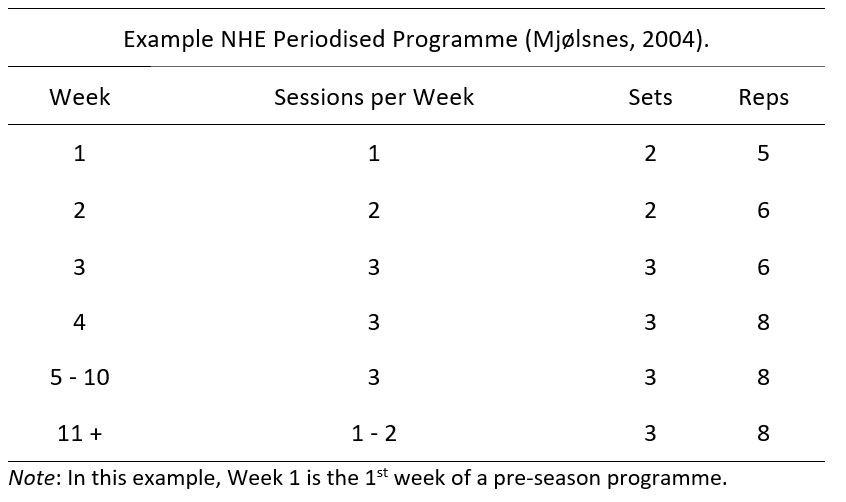

It has long been known that the eccentric contraction of the hamstrings during sprinting and high-speed running activities results in very high forces being applied through the hamstring muscles. These high forces have been shown to be strongly related to hamstring injuries [64]. As soccer training and match play involves many high-speed and sprinting actions, it is reasonable to conclude that players, especially those in the more sprint-demanding positions, will be at risk of hamstring injury. These injuries can take anywhere from 10 days to over 2 months to recover from, depending on the severity of the injury, and we should therefore pay close attention to minimising the risk of these injuries occurring. One exercise to achieve this, that has a large amount of clinical and soccer-specific evidence behind it, is the Nordic Hamstring Exercise (NHE). The NHE has been shown to significantly reduce both the risk of hamstring injuries, and hamstring injury severity in soccer players [1][28], while studies analysing its effects across multiple sports have shown the NHE to essentially halve the risk of hamstring injury [74]. The NHE has also been shown to have no negative effects on sprinting and jumping performance, while having a possible positive impact on 5 – 10 m sprint and CMJ height in elite soccer players when added to training programmes [35]. The way to perform this exercise is shown in the Figure below, and an example NHE programme is shown in the Table below. Due to the large amount of evidence supporting this exercise’s role in injury prevention in soccer, the minimal equipment required, and relatively few repetitions needed to have a significant effect, it is recommended that coaches consider adding the NHE to players’ gym routines.

Another exercise that can be added to players’ training very easily is the Copenhagen exercise. The main use of this exercise is to assess the risk of, and minimise, groin pain and injury as players with lower eccentric hip adduction strength have been shown to have higher incidences of groin pain and injury [68][69]. This exercise has been shown to increase eccentric hip adduction strength when added to the FIFA 11+ programme [27]. It is important to note that soccer players have been shown to be up to 14% stronger in their dominant leg for these exercises, and this should be considered when testing, monitoring, and training, using this exercise [68]. The correct technique for this exercise is shown below.

It is good to know these exercises, and their effects on soccer performance, but how do we implement these into players’ training? Visit the Training Programming and Considerations page to find detailed analysis and examples of how physical training should be integrated into technical and tactical soccer training.