Utilise effective and reliable testing methods to develop an in depth understanding of players strengths and areas to improve.

Testing entire squads in a laboratory is rarely practical, time-efficient, or cost effective. So, how can we substitute these ‘gold-standard’ tests with more easily accessible tests, while still collecting relevant and reliable results?

This section of testing includes both gym-based, and on-field testing, which are much more common places for testing with soccer teams than laboratories.

There has been lots of research into how well physical tests such as the VO2max and Lactate Threshold tests relate to soccer performance, with many indicating a strong relationship between performance in these tests and soccer performance from a physical standpoint, and in terms of competitive level.

Which tests should we use, and why?

As soccer is an intermittent sport, that involves many explosive actions during match-play, it is important that we cover all areas when profiling players. It is recommended that players should be tested on speed, power, agility, strength, anaerobic capacity, and aerobic capacity.

The aerobic capacity test is one of the most important, as up to 90% of a player’s energy production during a match is aerobic. Another good aspect of these tests is that they are one of the easiest to carry out with an entire squad. There are a few tests that could be used to test players’ aerobic capacity, each with pros and cons. For example, the University of Montreal Track Test involves continuously running around a track, marked every 25 m, at increasing speeds (+ 1 km·hr-1 every 2 min) until failure to reach a marker within the set time limit three consecutive times. This test gives a reliable prediction of a trained individual’s VO2max, however, soccer activity is rarely continuous as players are always changing direction and speed, and have periods of rest; so, is there a more appropriate test to use?

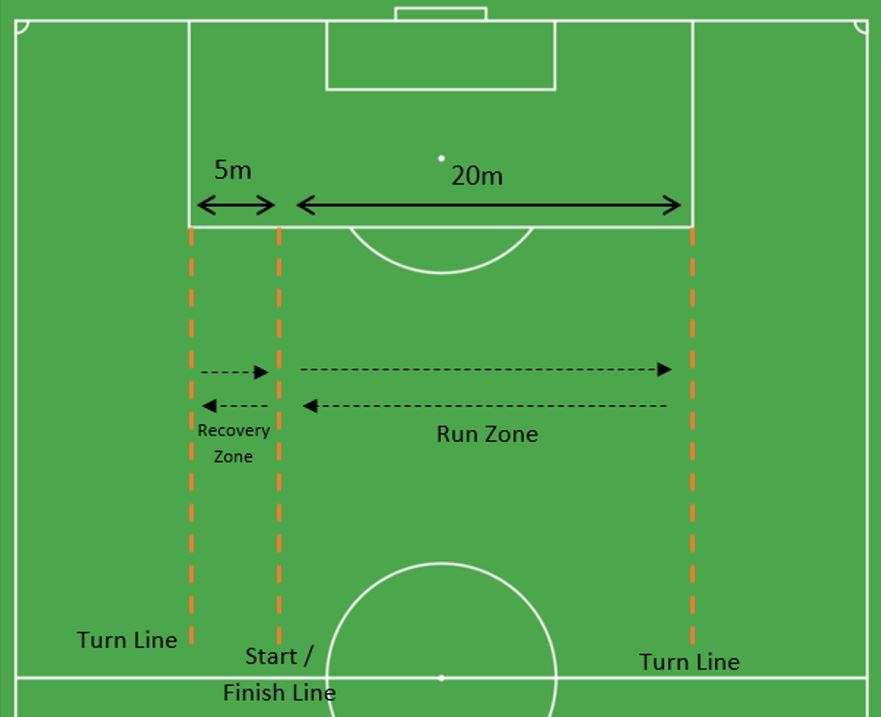

The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test 2 (YYIR2) is an intermittent 20 m shuttle run test, where players must continuously complete two 20 m runs (as shown in the diagram) in a set time, with a 10s recovery between. The time to complete the two runs decreases as the test goes on.

This test is one that requires both aerobic and anaerobic contribution, and its prolonged intermittent activity best mimics a soccer match, making it the most soccer-specific test.

The level of the YYIR2 completed is significantly related to speeds of a laboratory VO2max test, and therefore, estimated VO2max from the YYIR2 is also significantly related. Additionally, player’s maximum heart rate (HRmax) during the YYIR2 is strongly related to HRmax during a laboratory VO2max test. Yo-Yo test performance also correlates to the total distance, high-intensity distance, number of high-intensity actions, and number of sprints performed during matches [29][51]. In summary, the YYIR2 test gives us reliable, valid, and soccer-specific data for well-trained players [38].

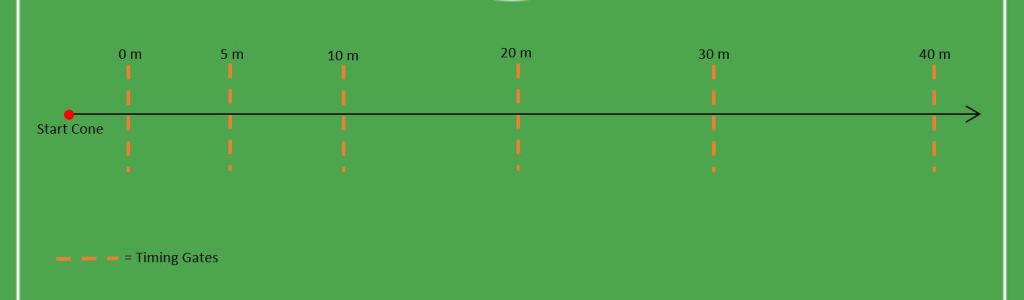

Next, we will discuss both speed and anaerobic capacity tests together, as to switch between the two only requires a small change of protocol. Firstly, the speed tests; these are normally done over distances of between 5 – 40 m, and in practice the distance used depends on what the coaches or staff feel are appropriate. During a match, 96% of sprints are less than 30 m in length, and almost 50% are less than 10 m [40][65]. However, protocols to determine maximal sprint speed typically use distances up to 40 m, with most using a rolling start, as this is the most soccer-specific, and minimises the contribution of a player’s acceleration ability.

Therefore, it is recommended that players should be tested over 5 – 40 m, with intervals as shown in the diagram below. If available, timing gates should be used as they give the most accurate measurements in this test, and each player should be given 3 attempts at the test, with self-selected maximal rest in between attempts [77].

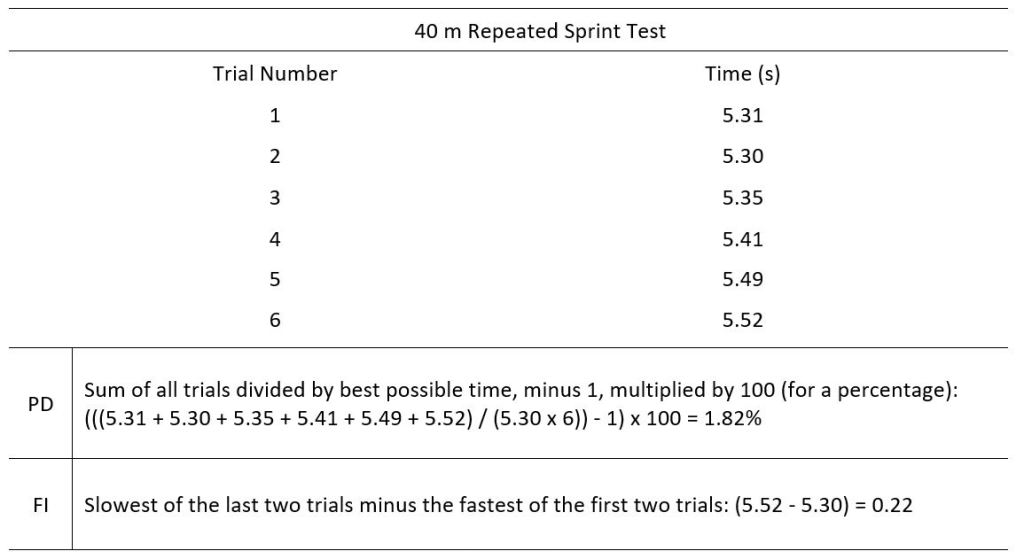

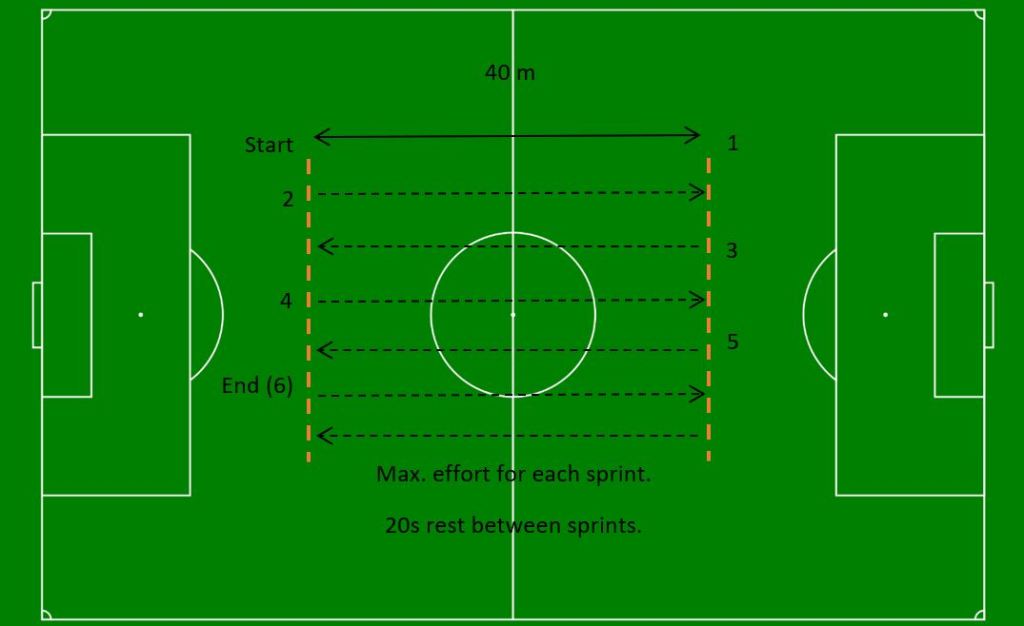

Secondly, the anaerobic capacity test, or repeated sprint ability test, is similar to the speed tests as it measures time taken for a number of sprints (20 – 40 m) with limited recovery (< 30 s). From this test we can calculate both Performance Decrement (PD) and Fatigue Index (FI), which are both measures of a player’s anaerobic capacity.

The description of the two measures, an example test, and a calculation is shown in the table below. The lower the PD and FI, the greater a player’s anaerobic capacity, as they can maintain anaerobic output over a prolonged period.

The repeated sprint ability test is very adaptable, and much like the other tests can be varied to give coaches and staff more useful and worthwhile data for them. The figure below shows an example of how this test should be set up and carried out.

Player’s strength and power can be tested very easily in a gym setting. The best way to test a player’s lower body strength is to do a true, or an estimated 1 repetition maximum (1RM) squat test, using a barbell back squat. A true 1RM test involves a player working up to a 1RM squat, whereas an estimated test involves completing a 3 – 5RM test and then 1RM being estimated from this. 1RM squat scores are strongly correlated to 10 m sprint performance (r = 0.94) [32]. Therefore, we can use the 1RM squat test, either true or estimated depending on movement proficiency, to assess a player’s strength capacity. Maximal strength also affects a player’s power, as the two are linked due to maximal strength improvements usually increasing a player’s relative strength. 1RM squat performance is also strongly correlated with jump height (r = 0.78) [32]. To assess a player’s power, we would typically use jumping tests as this gives us lower body power scores, which are far more useful for soccer coaches and staff than upper body scores. The two main tests that are used are the countermovement jump (CMJ) and squat jump (SJ), these two tests follow the same movement, however there is a pause at the squatted position before jumping during the SJ test. It has been shown that there is a significant relationship between a team’s average jump height and team success [4].

Lastly, we will look at testing players’ agility. These tests are similar to speed tests, with the addition of accelerations, decelerations, and several changes of direction, much like movement during soccer matches. A benefit of agility tests is that they can be done with and without a ball, and the scores compared to create a measure of skill with a lower difference between times indicating a higher skill level. A popular agility test is the 5-0-5 test, which is outlined in the figure below.

Players have a 5 m run up until they pass through the timing gates, and they then maximally sprint a further 5 m with either their right or left foot reaching the cone past this line, they then sprint back through the timing gates as fast as possible, and the time between passing through the timing gates is recorded. Players can complete this with and without a ball, and should be tested reaching the furthest cone with both their left and right feet to assess any asymmetry. This test has been shown to provide reliable, accurate, and repeatable data for agility [17].

It would also be useful for staff to monitor players’ heights, weights, and body composition within testing batteries as these can be used to assess maturation status, and lean body mass. It is suggested that these measurements be taken using a stadiometer, electronic scales, and calipers, respectively [16].

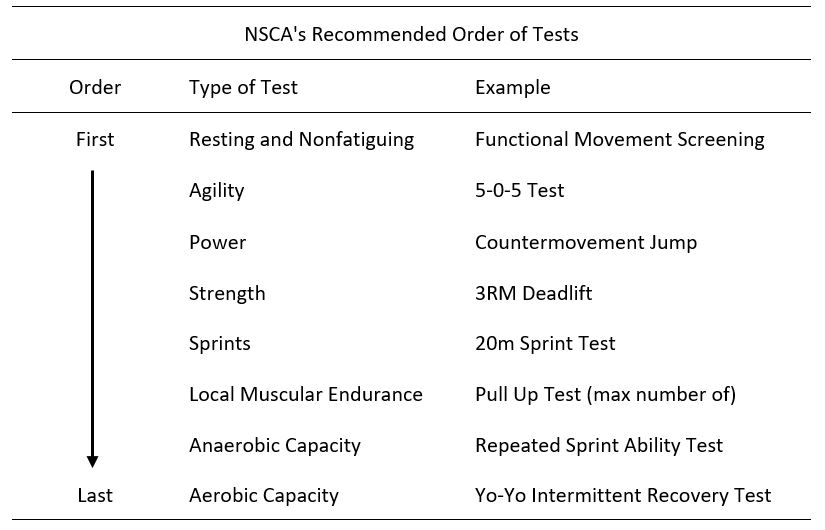

This section has outlined on-field and gym-based tests that can be combined into a comprehensive testing battery for use with soccer teams. The data collected from these tests will provide coaches and staff with physical profiles for each player, in a setting that is low-cost, requires minimal equipment, and is very soccer-specific. These profiles can then be used to prescribe training throughout the season. Testing should be conducted multiple times throughout a season to give staff initial benchmarks for players, and then data to see whether players’ physical capabilities are increasing or decreasing, and if their training is working. Testing should be carefully structured to allow the best data to be collected from players, and the table below outlines the National Strength and Conditioning Association’s recommendations for how to structure a testing battery.